ELECTRONIC TUNING

It seems there are misconceptions about the use of Electronic Tuning Devices (ETDs) and Electronic Tuning Apps (ETAs).

On this page we will look at ETDs and ETAs. Some theory about piano strings, Harmonics and Partials will be needed.

The electronic software and hardware options available to piano technicians today, are vastly different from what existed fifty, or even twenty, years ago. Early devices were quite limited. They were sometimes used in an ill-informed way, resulting in poor quality tunings and giving clients a bad impression.

First, let's have a quick look at the professional devices and Apps, and then discuss a bit about tuning.

For reasons we’ll go into further down this page, basic chromatic tuning devices or Apps for guitars etc are useless for piano tuning. The professional Tuning Device or App that you might see your piano technician using, belongs to an entirely different class, is specifically designed for the complexities of the piano, and is expensive software and/or hardware.

A BIT OF HISTORY:

In the late 1930s the first “Strobe Tuner” was invented by the Conn company, later taken over by Peterson who developed their own models and still produce some tuning Apps and devices today, though not for pianos. The current range is here https://www.petersontuners.com

There is a short explanation of the basics of strobe tuners here:

A FORWARD LEAP

A major forward leap came with the work of Harvard Professor of Physics and Electronics, Dr Albert Sanderson. His son Paul in a very helpful email to me writes that Dr Sanderson had “a love of the piano and a fascination for tuning”. Dr Sanderson and his sons set up electronics consulting company Inventronics, Inc. and in time started producing the Sanderson Accu-Tuner.

This compact stand-alone device was a huge advance in electronic tuning. It measured to an extremely fine degree of accuracy, and calculated inharmonicity and stretch (which we’ll come on to) in ways previously impossible.

I met Dr. Sanderson briefly at an event in the mid 1980s, and found him a most genial and approachable man. The Accu-Tuner is still produced and marketed by Inventronics, Inc., continues at the forefront of technical developments in piano tuning software and hardware, and is still offered as a stand-alone device. The website is https://www.accu-tuner.com/

PLATFORM DEVELOPMENTS

The rise of Laptop PCs saw the development of software programs (who remembers ‘programs’ – it’s all ‘Apps’ now!) capable of measuring piano scales and facilitating tuning.

In the early 2000s hand-held devices called Personal Digital Assistants or PDAs appeared, some with a version of Windows called the Pocket PC. Some tuning software was adapted for these devices.

The iPhone brought a new sleekness and sophistication, and other “smartphones” quickly followed. Windows Mobile was discontinued, and today Android and iOS operating systems are in parallel ubiquity. ‘Tablets’ have brought each operating system to bigger, highly versatile platforms.

As an aside – in Scotland, we still like this traditional kind of Tablet:

Developers of professional piano tuning software programs have made them into Apps for today’s Smartphones and Tablets.

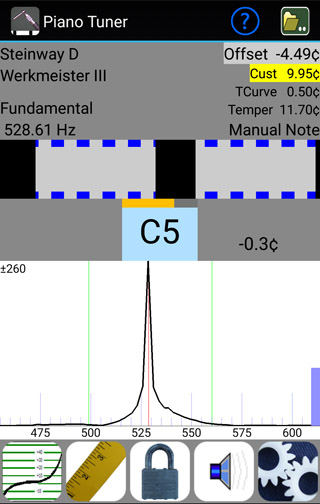

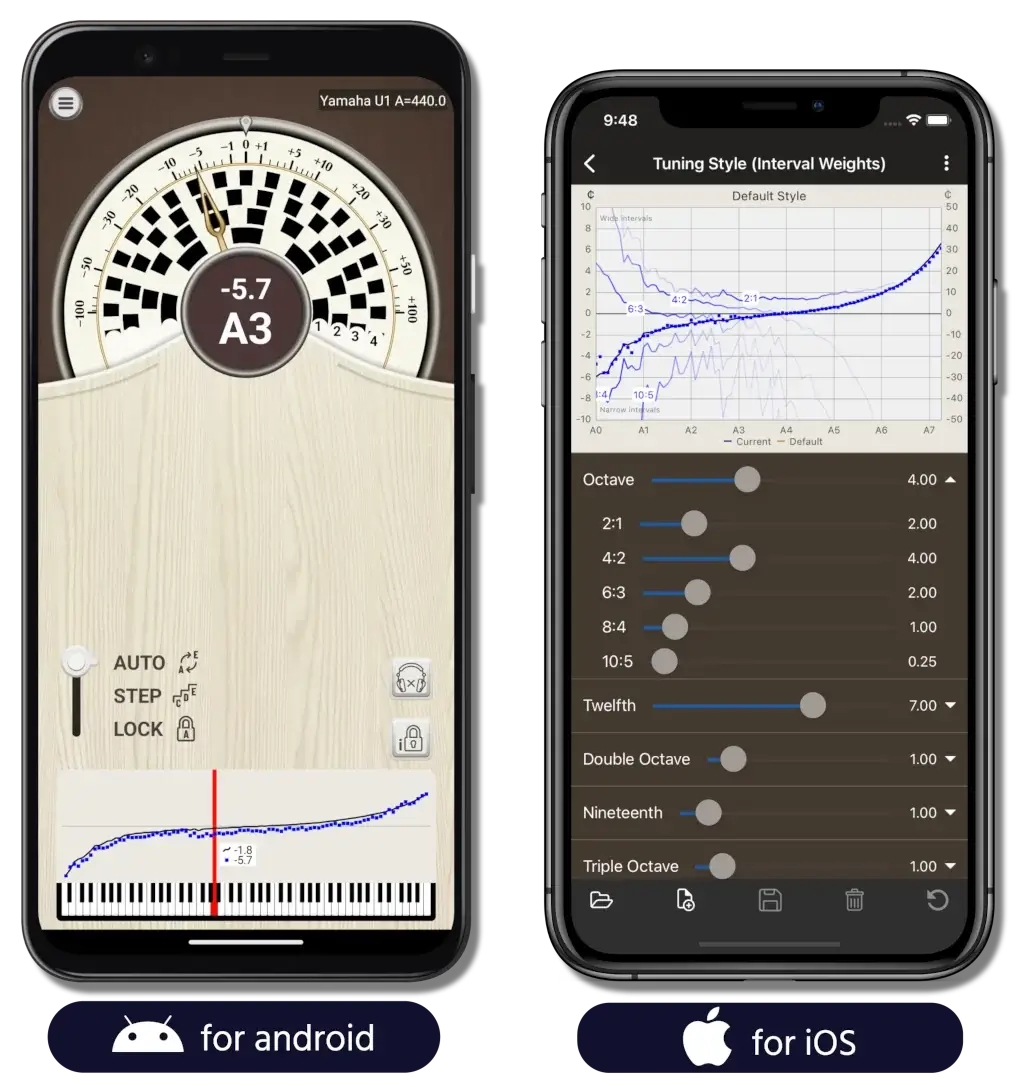

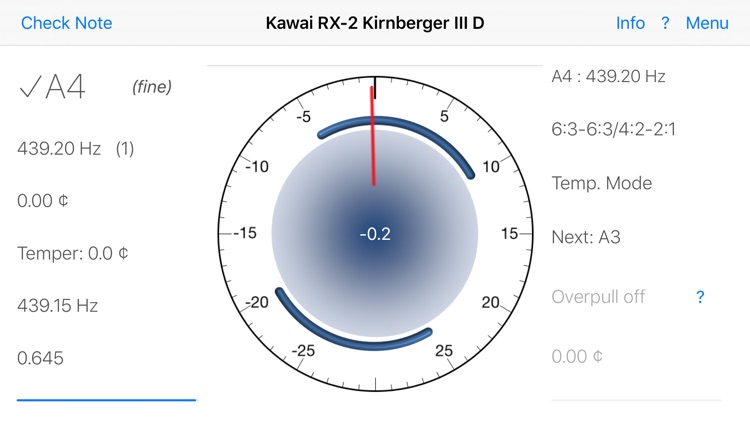

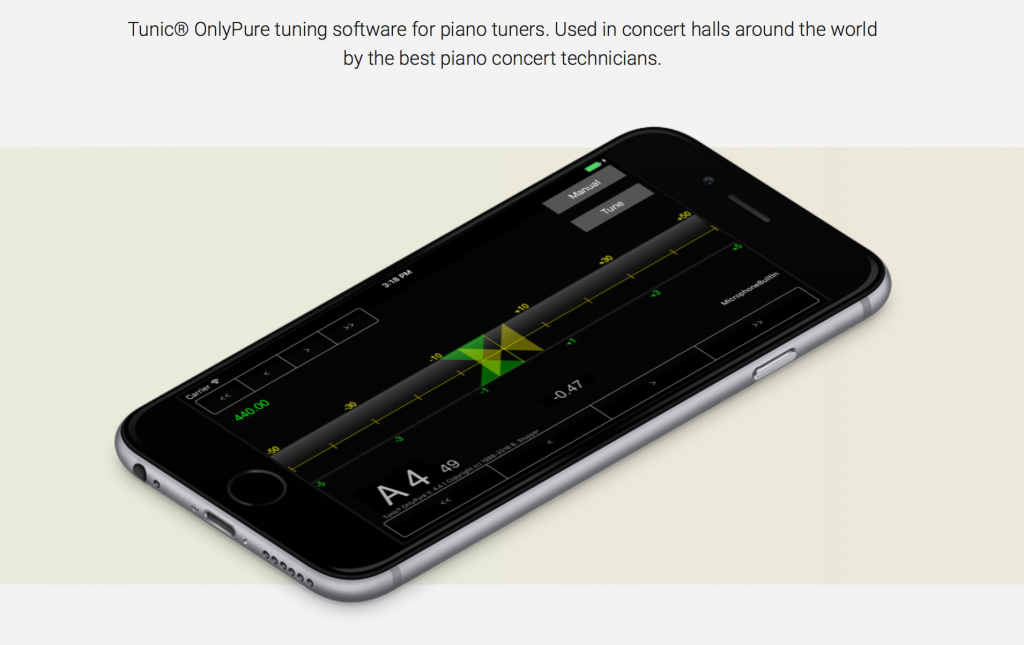

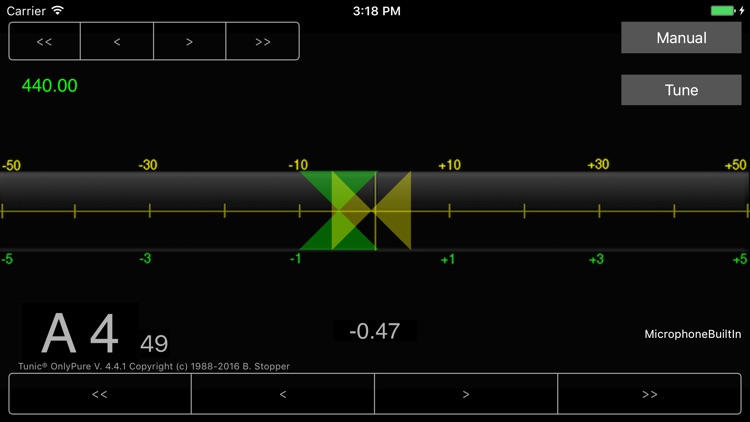

Photographs here are reproduced by kind permission of the various companies. Each naturally explains the merits of their own App or device, and I am not expressing a preference here. They are:

There is one other professional piano tuning software App, Reyburn Cybertuner, also for iOS. I’ve not heard back from them with permission to reproduce photos here.

IS IT 'CHEATING'?

Use of such devices or software is neither “cheating” in some strange way, nor a substitute for the human ear/brain. They are an extremely valuable addition to the armamentarium of the careful tuner-technician, and most of the world’s foremost piano technicians make use of one or other of them as an adjunct to aural skills.

To use them properly, you need to have a solid understanding of the variables of piano tuning.

HERE GOES WITH SOME THEORY

Many struggle with tuning the six strings of a guitar. A piano has over 220 strings.

The dozen or so bottom notes in the bass are single strings; a steel music wire core wound with copper (usually two layers, though the photo below shows a very high quality large upright piano with single-layer copper windings). These are called monochords.

When a guitar string is plucked or a piano string struck, it doesn’t just move along its whole length. It splits itself up into a complex mix of nodes and antinodes, such that it moves as halves, thirds, quarters and so on.

This is beautifully explained and illustrated in this YouTube video:From 7:00: "The thing to remember is that the string wants to do this so if we had hit it with an impulse – if we had hit it like a guitar string, all of these modes would be singing together at the same time, and that’s what gives the guitar string the characteristic sound that it has. It’s the combination of all those frequencies playing together, simultaneously, at different amplitudes that makes the sound of the guitar, or a violin, or a harp or a piano. Barring any small details about tuning. The balance, or the relationship, between the amplitudes of those different harmonics playing together at the same time is what makes those instruments have their characteristic sound".

Each of these frequencies within a vibrating string is called a Harmonic. The First Harmonic is called the Fundamental, the whole length of the string (in the YouTube video it has a frequency of 11Hz). The Second Harmonic is the frequency of the string moving as two halves – that’s twice the frequency. The Third Harmonic, three times, and so on. This series of movements within a string is called the Harmonic Series.

Every string in each of the piano’s 88 notes produces its own Harmonic Series. This is not the place to go deeply into the arithmetic. The frequencies of the Harmonic Series of all the notes interact with each other in very complex ways. To learn more about this, you can obtain one of the technical books.

There is a very nice Harmonic Series here, starting at 100Hz. Click and hold on each 'string' to hear the tone, IF you are listening on a laptop or notebook, you might not hear the fundamental as 100Hz may be too low for the speakers:

https://alexanderchen.github.io/harmonics/

Here is a YouTube video of the same thing:

NOW WE COME TO A COMPLICATION

So far we’ve talked of Harmonics, which are perfect mathematical relationships. Now consider this:

Fence wire is quite thick. But over a good length like that, you could probably “twang” it quite easily. If it was tight enough, it might even produce a musical tone.

Now imaging cutting a short length of it, perhaps about 6 inches (15cm). This short piece would seem much less flexible – much stiffer somehow than the long length stretched between two fence posts. You wouldn’t be able to twang it.

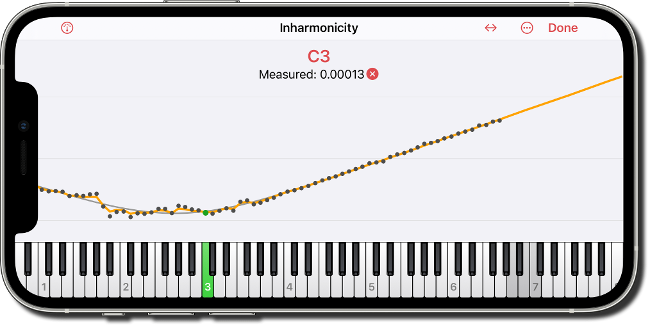

Something like this happens with the Harmonics within a vibrating piano string. The shorter lengths are relatively stiff (its more complex than this!) and the frequencies they produce are slightly higher than the perfect theoretical frequencies of the Harmonic Series. This effect is called Inharmonicity, and it gets greater towards the low bass and high treble.

Dealing with Inharmonicity is a major aspect of piano scale design and of tuning. How a manufacturer incorporates inharmonicity aspects into the scaling of a piano has a substantial effect on its tonal qualities (along with many other tonal factors of course).

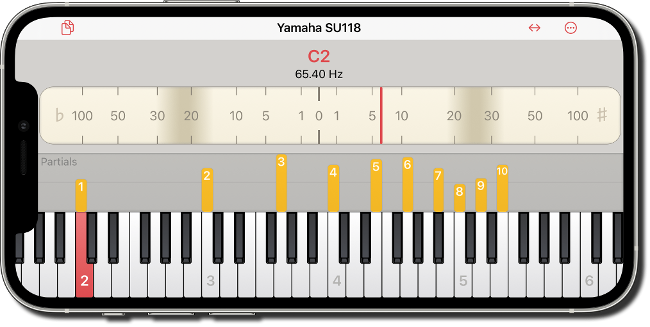

The actual frequencies produced by a vibrating string are referred to as Partials, to distinguish them from theoretical perfect Harmonics.

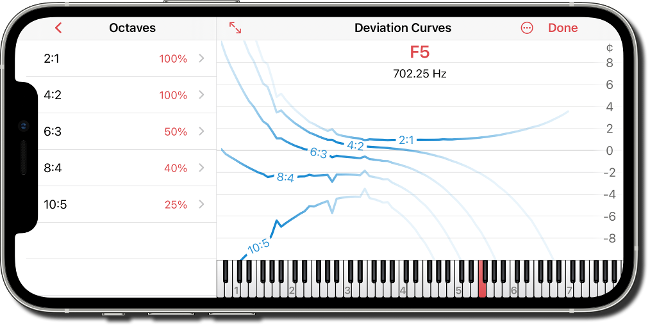

The point of all this is that piano tuners need to apply stretch, to get the piano to sound good. Stretch means that tuning is adjusted to take account of the deviation of the strings' partials from theoretical perfect harmonics. Modern ETDs and ETAs – those shown here – can analyse the component frequencies of the vibrating strings across the whole range of the piano and then suggest optimal degrees of stretch.

Here is a photo of the Frequency Spectrum Graph produced by PianoMeter running on my Huawei 10" tablet, for note A2 on my own upright piano. A2 has a Fundamental frequency of 110Hz.

It shows a nice series of Partials!

Showing relatively little power at the Fundamental- the First Partial - is normal for bass strings. Then we have the Second Partial, whose frequency 220Hz corresponds to the A an octave above. Then the Third partial 330Hz, the frequency of C an octave and a fifth above, then the Fourth Partial, 440Hz, two octaves above, then the Fifth Partial, 550Hz two octaves and Major Third above. And so on.

Here is the spectrum for note C4 – middle C – on the same piano, showing the same frequency relationships in its Harmonic Series.

So today’s Electronic Tuning Devices and Apps are extremely sophisticated and very far removed from earlier technology. They do not replace the skill and discernment of the tuner in responding to the individual piano and in manipulating the tuning lever to achieve a stable tuning. But they do help with certain aspects and can measure the piano in ways that contribute to a superb tuning.

There is a more about tuning theory and the complexity of the piano scale in the About Tuning page of this site.

You might - or might not - enjoy a YouTube video I made to demonstrate the phenomenon of "beats", basic to all piano tuning.

In the video, two sources are playing a 440Hz sine wave tone at the start. One of the sources is then gradually increased in frequency to about 460Hz, then back down to 440Hz. As the frequncy starts to increase, a pulse of increasing speed can be heard between the two tones, going from a slow wah-wah-wah to a rapid thrumming at 20Hz. These pulses are a kind of interference pattern between frequencies that are near but not identical. In piano tuning they are called 'beats' and are basic to tuning.