Piano Tuner in Inverclyde, Renfrewshire, Glasgow, the west of Scotland and beyond.

The mythos of the Bechstein Brand

Scotland - for that matter, the UK - is awash with Bechstein pianos. But they are all over a century old.

The Bechstein company employed to a remarkable degree before the First World War, a marketing concept you might think of as modern - "brand value". Carl Bechstein established brand value so successfully that the effect has lasted well over a century. This means that the pianos have been kept operational, and their prices high.

The Oldest Bechstein

Here are some photos of an interesting Bechstein piano, courtesy of David Winston, proprietor of Period Piano in Kent.

This is thought to be the earliest Bechstein piano still extant.

Here is the serial number, on the soundboard:

That's a very early Bechstein serial number!

The straight side of this piano is most unusual - in fact it isn't straight, but has a bulge at the top end, a remarkable design experiment by Carl Bechstein.

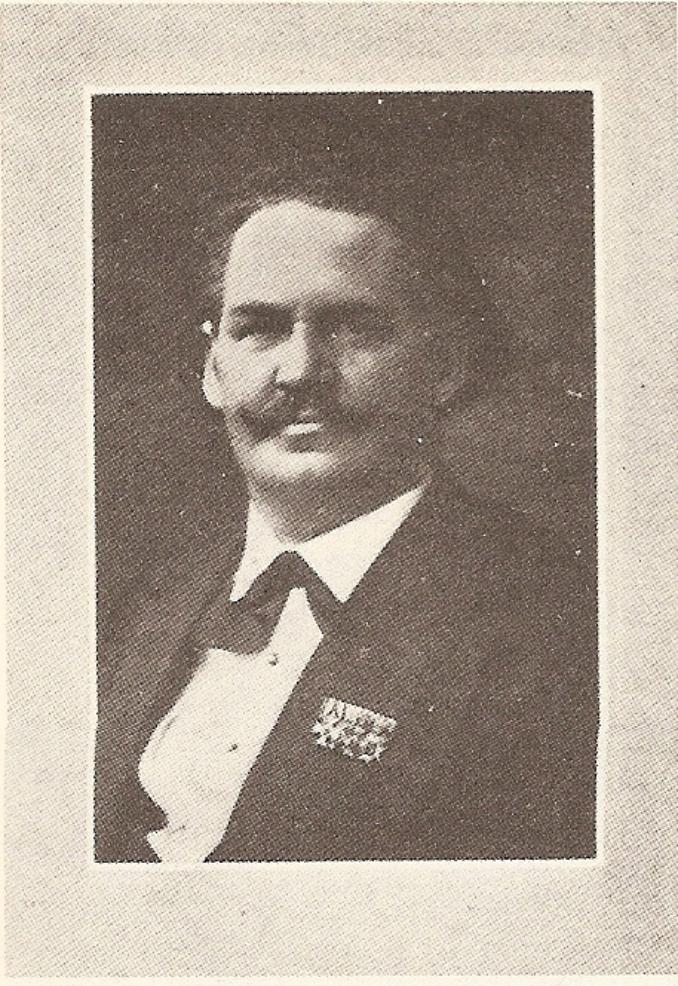

Carl Bechstein

Carl Bechstein was born in Gotha in 1826. By the age of 22 he had risen to become foreman of G. Perau, a well-known Berlin piano company of the time.

Alfred Dolge the great American piano expert at the start of the 20th century wrote:

After four years' faithful service wanderlust got the better of Bechstein, and we next find him at London, later at Paris, studying under that genial empiric, Pape, and getting an insight into modern business methods with Kriegelstein.

Equipped with new experiences in piano making, a thorough knowledge of Parisian commercial tactics, enriched with broader views, world-wise, Bechstein returned to Berlin and built his first grand piano in 1856. A man of the world, amiable, even magnetic to a certain degree, he easily attracted artists and litterateurs to himself, gaining thereby a publicity which redounded largely to the ever-increasing prosperity of his business. Carl Bechstein received numerous decorations, both from his King and Emperor, as well as other rulers, and was appointed purveyor to the courts of nearly all the reigning emperors and kings of Europe. He died at Berlin in 1908 at the age of 82.

Dolge's book was published in the same year that the two Bechsteins featured on my No WD40 Please page were manufactured, at the height of the company's success.

Cyril Ehrlich in the excellent The Piano A History says of Dolge's suggestion that Carl Bechstein visited London early in his career:

Dolge's suggestion that he spent part of his wanderjahren in London is probably wrong: Bechstein's first visit appears to have been for the 1862 exhibition.

Ehrlich also observes regarding Dolge's comment on Carl learning business expertise in Paris:

It is likely, however, that the latter skills as practised in France at that time were to prove less useful than friendship with Jean Schwander, whose piano actions were soon to be used by first class makers throughout Europe. In 1853 Bechstein commenced business in Berlin making a few uprights, and in the autumn of 1856 he scored a notable success when his first grand piano was inaugurated by von Bulow with a performance of the Liszt Sonata.

Thus began one of the most significant relationships between instrument maker and virtuoso in the history of music, each stimulating the other to higher achievement. Convinced that until then 'nothing really outstanding had been produced in Germany' Bulow did everything in his considerable power to help Bechstein establish an international reputation. It was because of his recommendation to Klindworth that Bechstein was encouraged to take part in the 1862 London Exhibition, and his loyalty to the firm probably accounts for Bulow's refusal to play Steinways in America.

Carl Bechstein certainly seems to have combined eagerness for the latest technical advances with a very shrewd marketing strategy. He had sales ambitions for, and success in, all of Europe and the UK as well as his home market in Germany and there was also a showroom in St. Petersburg. From the late 1880s the company was particularly successful in building a market in the UK. Queen Victoria, no less, acquired a Bechstein piano in the 1880s (sources vary on the exact year).

Dr Alastair Laurence in his excellent book Five London Piano Makers notes regarding the aggressive, name-dropping marketing materials produced by Brinsmead pianos in the late 19th century that:

Such advertisements were only emulating the kind of self-publicity already commonly found among American and German piano makers, where Bechstein in particular was constantly 'puffing' and name-dropping. There was hardly a crowned head in Europe who did not have the pleasure of the ownership of a Bechstein grand; and Carl Bechstein himself, with his huge ego, was determined to make sure that the world knew of this fact.

A chapter endnote mentions a Bechstein publicity brochure in Dr. Laurence's collection, that "has forty-three royal heads of state name-dropped on its title page as being the firm's customers."

Bechstein Hall

A significant promotional strategy of the major piano makers of that period was to establish recital halls near their showrooms, to show off the pianos in use. In 1901, Bechstein opened Bechstein Hall in Wigmore Street London, next to their large showroom. According to some sources, Bechstein was at that time the largest piano dealer in Britain.

And then, the First World War came. That unparalleled shock to the world order resulted in many changes, including the falling from grace of German piano maker C. Bechstein.

The company managed to keep trading in Britain at the beginning of The Great War but in 1916 all their UK property was seized and the showroom and Bechstein Hall closed, under the Trading with The Enemy Amendment Act 1916. What was Bechstein Hall is today Wigmore Hall a favourite recital venue of mine.

Bechstein never recovered their dominant UK market position after the Great War. Between the wars and after the Second World War, things were tough economically. There was less demand for grand pianos - an expensive item - and things German were out of favour in Britain. German Biscuits, then and now very popular in Scotland, became Empire Biscuits .....

Between-the-wars pianos are suddenly all Challen and Chappell and other English makes. The second world war saw the destruction of the Bechstein factory in Berlin and the loss of valuable timber stores. In the decades since 1945, the Bechstein company has been through various ups and downs of fortune, details of which can be found in online sources. Currently the company appears to be in the ascendant again, producing very fine instruments.

Concert pianist Sir Stephen Hough formerly had on his website/blog an excellent essay about Bechstein, with reflections on the rise and fall of home pianos, and the ascent of Steinway. Sadly his current website does not include these writings. His 2020 CD of Schubert Sonatas (see link at bottom of this Page) is played on a C. Bechstein piano.

Bechstein Made in London?

Yes! The following information is new to me as of August 2023 (though some of it is available on Wikipedia). Thanks to Andrew Giller and others in a piano technical group, for information, and to Mark Bolsius of Touchstone Pianos Australia, for the photos.

Andrew Giller writes:

"The Bechstein Piano Co. Ltd (operating 1924 - 1939) leased a huge factory just off Tottenham Ct Road, near Warren Street Tube. Started baby grand production for two models 4’ 6” & 5’ around 1933, frames cast in the U.K., parts from Berlin. Yes, they have their own serial no. range from 240,000 and a few uprights were made as well. These pianos were all part of the 30s boom for small grands and proved nicely assembled examples. The factory was closed around June 1940 by receivers".

In response to my surprise in learning that Bechstein started up their own London factory, Andrew writes

"Yes, their own factory. It was set up by the former pre WW1 London manager Max Lindlar (original term 1884 - 1912) & Carl Bechstein jnr or second son. Max is pulled out of retirement etc. The factory is well hidden at the back of the Grafton Hôtel in Whitfield Place. Still there as flats!"

Andrew also credits the renowned piano expert Dr. Alastair Laurance for some information:

"I also have... never seen any evidence of badging from another maker. Rogers were close, but only in copying and scale design. Hence their nickname of English Bechstein! Credit to Alastair Lawrence in PTAN April 2008 who briefly tells us the factory manager is a German, Max Poser who originally was a Chappell designer."

The serial numbers for these London-made Bechsteins were different from the Berlin pianos, and start from 240000. Here, courtesy of Mark Bolsius, are a couple of photos of a London Bechstein that made its way to Australia:

Bechstein in Berlin do not today have much in the way of information about this London Factory era, it seems, due to wartime loss of records.

Bechsteins Old and New

As a result of the company's phenomenal marketing success more than a century ago, Bechstein is probably the most common single piano brand in Scotland. But all (well almost all) pre First World War.

Someone should do a PhD thesis on the enduring success and cachet of the Bechstein brand. Because they are perceived to be especially good, Bechstein pianos have been considered worth refinishing and rebuilding and their values have remained high, while many English-made pianos of equal quality have long since been junked.

This perception of "specialness" regarding these old Bechstein pianos is at least as much due to the brand value established by Carl over a century ago, as to the technical quality of the pianos. A while ago I tuned a beautiful German Duysen grand piano of 1901 - a piano fully the equal of a Bechstein, but who ever heard of Duysen?

I am not suggesting for a moment that Bechstein pianos were not or are not excellent - they were and are - or that I do not like working on them - I do. But they were not magically, mystically pianistical! They are not better than the very best English makes of the period, many of which have long since been destroyed.

Where the reputation of English pianos suffered, though, was in the proliferation of really cheap, poor quality pianos that started to be assembled in great quantities by numerous small workshops from the late 1880s, to meet a fast-growing lower middle class demand for cheap parlour pianos. The top British pianos were always just as good as the Bechsteins and other German makes, but the German industry never developed a "cheapo" end. Perhaps as a result of that, German pianos, of whom Bechstein were the most aggressively marketed, enjoyed a higher overall reputation.

States of Repair

Many of these old Bechstein pianos have never had any regulation in a hundred years and are very worn. Others have had some cosmetic refinishing but are all original, and worn, inside.

A school showed me a large Bechstein grand that had been gifted years ago. It had a relatively modern finish, badly done on top of the old French Polish and now peeling. And replacement legs. But a glance inside immediately revealed that it was old. The school music staff were surprised to learn that the piano was made in the late 1880s. They shouldn't have been surprised - it sounded and felt like a piano of that age. By far the oldest working piece of equipment in the school. Remarkably, although the action was worn and badly out of regulation, the only thing actually broken was a single cord loop. This meant that the note would not repeat, and I had to take the action out and renew the loop:

Here is the hammer rail with hammers attached, set aside. This was taken off to allow access to the action component (wippen & lever assembly) with the broken cord loop:

The broken cord loop is shown here. In 129 years, the only part to have broken. Readers familiar with piano actions will spot the rocker capstans, yuk. But that's another story.....

A new loop was made, using the appropriate type of cord, and you can see it here, with the repetition spring hooked into it:

Schools considering replacing acoustic pianos with digital instruments do well to consider durability.

Digital keyboards are versatile tools. But they're best as additions to and not substitutes for, a school's pianos. How many digital pianos bought in 2015 will still be playing, with only one tiny broken part, in 2145? How many, actually, in even ten years' time?

Neither Carl Bechstein nor, I suppose, any other top piano maker, envisaged that their pianos would still be in service after 130 years. They just built for quality, and the survival of these instruments is a tribute to the craftsmanship and materials of the late 19th century.

Models of upright and grand

It's beyond our scope here to detail the various models of upright and grand pianos made by Bechstein over the years. There is good information available on the websites of various piano dealers. Experienced piano rebuilders and retailers also have views on which years saw the highest manufacturing quality from the company.

Many piano makers produced special art cases, sometimes by noted designers. Here is a very nice art case Bechstein Model 9 with a design by Walter Cave.

Jack Assist Spring actions

Some Bechstein upright pianos had an action with an extra spring (for each note), intended to increase the speed of repetition. Repetition means how fast you can repeat notes without letting the key all the way up.

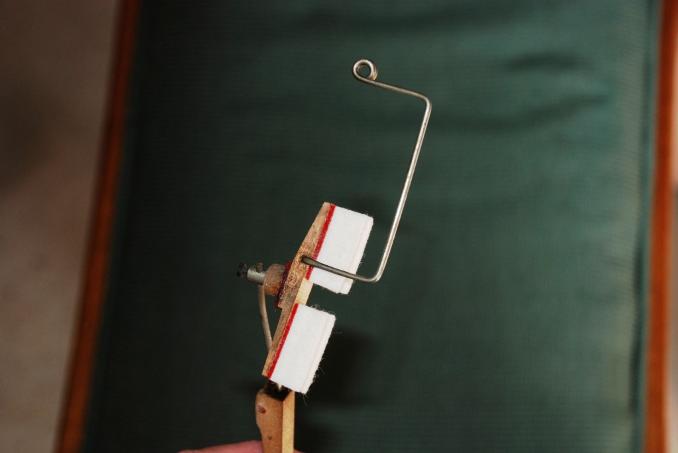

Schwander and at least one other action maker produced actions like this. The extra spring and loop arrangement can be called a Jack Assist Spring.

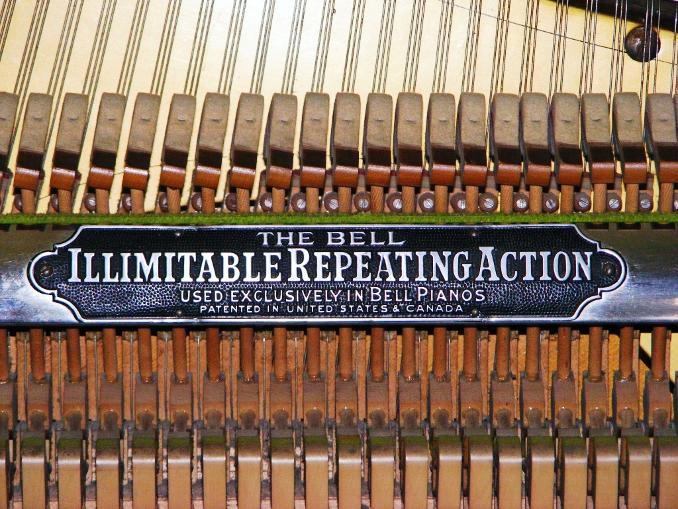

Some fine quality large upright pianos made by the Bell Piano & Organ Company of Ontario, Canada had actions like this, and they gave it their proprietary name, the Illimitable Repeating Action. Fancy stuff!.

Photo courtesy of Mr Kevin Schick

Today some new piano action designs incorporate extra features with the same aim of improving repetition. Among these the most notable is probably the Fandrich upright action. You can see the Patent application for the Fandrich action here

Piano and retired bass string maker John Delacour says that he has known 'restorers' in the course of working on these Jack Assist Spring actions, to simply snip off the extra springs, not wanting to be bothered with them. That's a kind of vandalism (though having spent considerable time persuading these springs to go back into the loops after a repair, I sympathise).

The photo below shows the spring and the cord loop that protrudes through the jack to engage with the spring. This was additional to the normal coil spring under the jack heel, and theoretically helped to relocate the jack tip quickly under the hammer butt.

A view of a single note, showing the additional Jack Assist Spring:

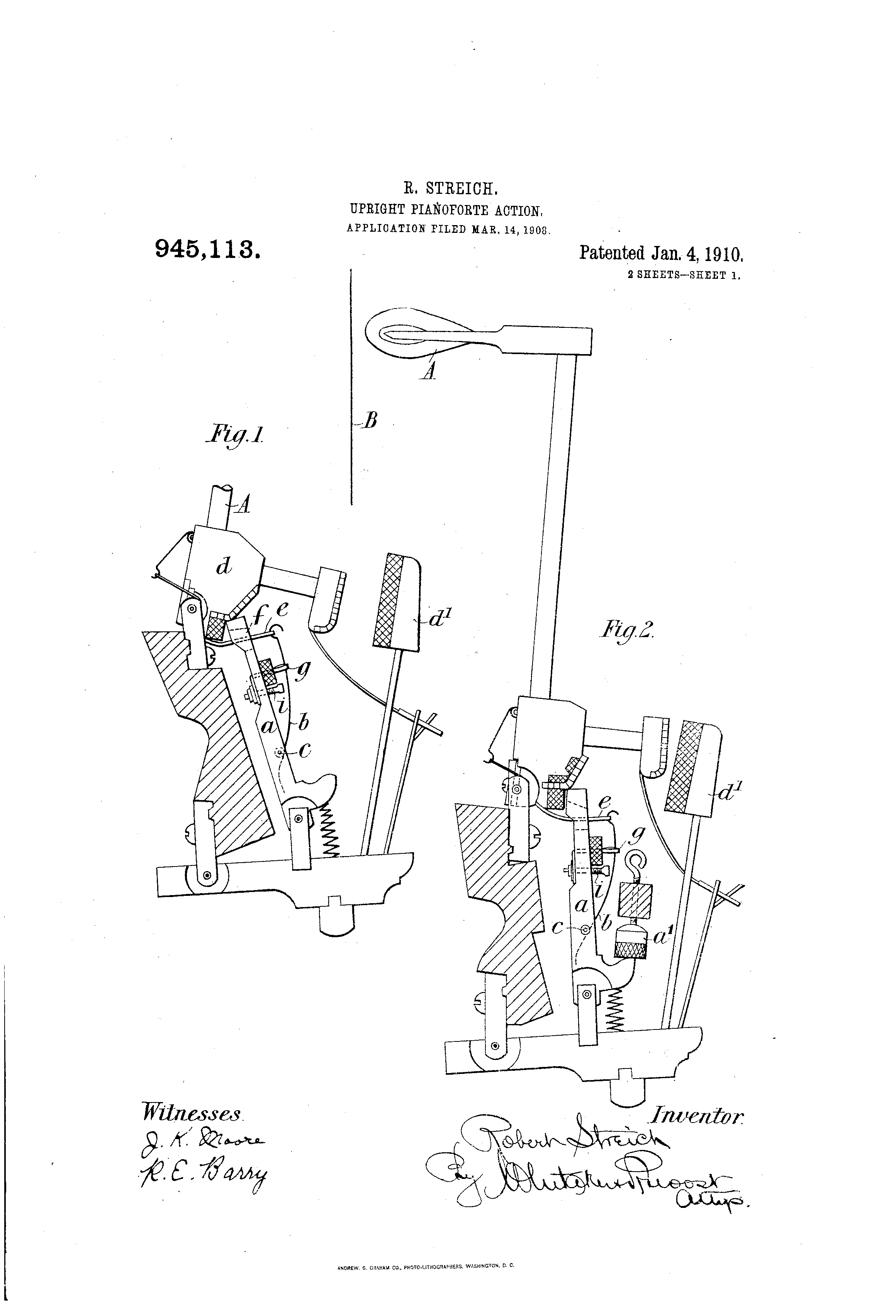

I have discovered that there is a US patent on this type of action design, US945113A from 1910, by a Mr. Robert Streich. Here is one of the two original patent drawings:

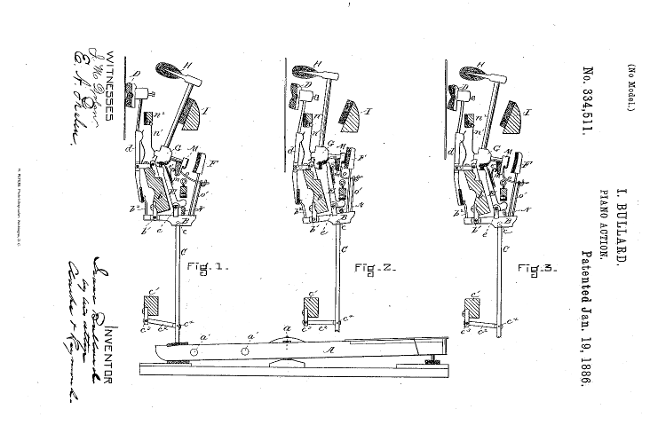

And here is another slightly earlier patent application with a jack assist spring arrangement of a different design - drawing below:

Large, high-quality pianos like Bechstein often had extra little dampers called 'fly dampers' fitted to the bass notes, to help damp those long strings more effectively when you let the keys up. Here is a typical set of bass fly dampers on a Bechstein Model IV

Counterbalance Wires?

Fly dampers like those above are fairly typical. But I was mystified to find on an 1880s Bechstein upright action, a set of wires sticking up from the bass dampers with nothing attached to them:

I hadn't seen this before, but have since found the same action in another Bechstein of similar age. The suggestion has been made that they may have been called Counterbalance Wires, adding mass to the damper heads and vibrating in a way that helped the dampers to seat more efficiently on the strings. A first thought was that something had been removed from these, but it's evident that nothing was ever there. Here's a closeup of a single damper with its Counterbalance Wire. The original damper felts on this piano were hard, noisy, and inefficient, so I fitted new damper felts, which is why they are so white.

A Century of Grime

Over the course of a century, dust and grime accumulates on the key-bed. This is a Bechstein Model 10, a straight strung Bechstein model, from 1911. The key-bed is shown halfway through cleaning - it needed it! Of course it isn't only dirt that needs dealing with after a century of use. Various action problems were corrected at the same time, making the piano play much more reliably.

The Bechstein Model 10, a parallel-strung, or 'straight-strung' was of high quality. Here's a front view with the action out, showing the parallel stringing (not overstrung). The offset bass bridge 'apron' on these pianos has an interesting shape.

These huge uprights are of an age that means they will require restoration/rebuild. But it's worth doing, because no pianos of that scale are being manufactured today (the tallest new upright pianos are the Steingraber 138 and the Bluthner Model S)

This is a Bechstein promotional film from 1926 (the year my mother was born).

Here is pianist Sandro Russo playing Liszt's Consolation No 3 beautifully on Franz Liszt's own 1862 Becshstein:

And here is pianist Sequiera Costa, whom I heard in recital some years ago in Wigmore Hall (formerly Bechstein Hall - see above) also on a modern Bechstein concert grand piano.

And, coming full circle, as it were:

It always seems to me when I hear new and very beautiful-sounding modern Bechstein pianos, that the 'tonal concept' belongs in the same family as all the 120 year-old ones that I've tuned.

Documentary film released March 2018:

"Resonances, the latest documentary by award-winning director Tom Nitsch, pays tribute to the fascinating sound of the Bechstein pianos, gives glimpses of the C. Bechstein manufacture and features several great pianists".

Sir Stephen Hough performs Schubert sonatas on a C. Bechstein Model D piano, on the Hyperion label:(As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases linked on my website)

Carl Bechstein (aka Ronnie Barker?)