Piano Tuner in Inverclyde, Renfrewshire, Glasgow, the west of Scotland and beyond.

Tel: 07714959806

Lindner pianos

Here's a photo of something unusual:

What is this, and what's unusual about it?

It's a Lindner upright piano, and what makes this one a little rare is that it's in full working order. Photos on this page are reproduced by kind permission of the owners of the pianos.

The story of the Lindner pianos is interesting. In 1961 the Rippen piano company of the Netherlands set up a subsidiary company in Shannon, Ireland, under Irish government incentives to attract new employers.

At the time, the trend was for smaller upright pianos. Post-war house-building brought houses and apartment blocks with smaller rooms and lower ceilings. This along with different fashions in décor, meant that large traditional pianos seemed stylistically out of place. It was the era when fine old panelled doors were covered in hardboard.

The designers at Rippen saw that a smaller, lighter piano would offer advantages. So the brand new Shannon factory would produce unique new designs, engineered for portability and modern looks.

These lighter pianos were much less costly to transport. For shipping from the factory the key-beds could be folded into the body of the piano so that two pianos could be crated together in a much smaller space. The retailer would then fold the key-bed out and secure it. Weighing only around 75 Kg, they were easier to deliver, and the small size and neat plain design looked more contemporary.

Credit must go to the Lindner designers for their ingenuity in reducing the weight of an upright piano. Nothing was changed in the basic design of piano operation, but much thought evidently went into how things could be made lighter.

For a start, instead of the supporting frame of the piano being the usual extremely heavy solid cast iron plate, the Lindner designers opted for a frame made of welded rectangular-section steel tubing. You can see the rectangular-section tubular frame in this photo:

A closer view:

The strings, bridges and soundboard are of conventional materials.

The hammers too are conventional. Piano hammers are little wooden mouldings covered in highly compressed sheep's wool felt. Usually the hammer shanks rest on a wooden hammer rest rail having a strip of baize material, but in the Lindner action, the ends of the hammers themselves rest on the rail baize.

I vaguely recall that the earliest Lindner designs used foam rubber instead of wool felt/baize for some cloth parts like the rail above, and that it was found to perish and crumble quickly.

The Lindner designers were not the first to try plastics in piano actions but they made much more extensive use of plastics than had been tried before. You can see above that the damper heads are plastic, though the felts on them are conventional. Instead of the damper heads being attached to round steel wires on wooden levers, the Lindner action has square-section metal alloy rods attached to plastic flanges.

A weight saving is also made with the backchecks; instead of wooden heads on steel wires, they are stamped metal alloy. Cord and cylindrical plastic caps are used for bridles instead of braided tape and leather ends.

The acton design eliminates a relatively heavy wooden part called the Wippen, which normally supports several action components. Its function is still effectively there, but clever design with plastic and lightweight alloy means it's not a separate component.

The rear of the keys, seen above, show where a significant weight saving was made: the keys themselves are hollow plastic. Here's a complete key, out of the piano:

A view of the underside:

Closer view of the front of the key, underside:

General view of plastic keys:

And from the side:

Normally, piano keys simply rest at the middle on felt washers on a central wooden 'balance rail'. When you press them down at the front, they go up at the back, and operate the action for the note. In the Lindner pianos, the keys are held in place by, and pivot on, a small metal leaf spring:

So what's the problem with these nice little pianos? Why is the fully-functioning one at the top of this page rare?

The difficulty is that while the design process was forward-looking and innovative, the materials available at the time simply weren't durable enough. Parts started to get brittle and break. An example is the leaf spring that you can see above, on which the key pivots up and down. It's quite common for them to break.

Keys themselves can also break, perhaps because of a frustrated player pounding on them when the failure of another part meant that the note wouldn't play reliably

The other common fault is with the plastic hammer flanges. The photo below shows a hammer, shank, butt and flange assembly:

You see that the hammer butt (into which the wooden shank is glued) is plastic, as is the flange which secures the whole thing into a U-section aluminium action rail. Here is a closer view showing a part on the flange that frequently breaks:

If you look closely at the top left side of the flange you see that the end has broken off. This is significant because that part, in conjunction with a small flat square metal leaf spring, holds the flange/butt/hammer in place on the rail. When it breaks, the whole assembly comes out of the rail and won't work. Here are some broken flange ends, and leaf springs which have fallen out. I retrieved these from one of the pianos on this page. Not the one that's all working!

June 2024:

Mr Grant Benton in England, to help a friend with a Lindner piano back in 2016, redesigned and 3D printed two action parts for Lindners, offering some for sale on Ebay. (Photos below (with permission): However, while such parts can be obtained - from time to time at least - I do not offer a service to repair Lindner pianos. Thirty years ago I was willing to remove a Lindner action to see what could be done. But now these actions are thirty years older and thirty years more brittle. An owner would have to take the financial risk of other parts breaking when the action is removed, and it just isn't worth it. Such work would have to be the preserve of keen and able do-it-yourself repairers.

Lindner upright pianos appeared under various model names: Topic, Cameo, Festival and the Lindner name itself.

According to Mr. Anton Rippen, who worked in the Shannon factory, some 40,000 pianos were made there between 1961 and 1971. The Lindner company went into liquidation in 1975. No replacement parts are commercially available for these pianos.

It's a pity that the plastic parts and the leaf springs were not more durable, because the pianos had a well-designed stringing scale and they sound good for their size. Also they seem to have very good tuning stability. One technician has pointed out that the frame being tubular steel rather than cast iron, would give it a similar coefficient of expansion to that of the strings, which could be a factor in tuning stability.

There is an advert here for Lindner pianos in The Sydney Morning Herald of March 1967 (gentle reader, I was nine!).

Piano technician Mr Pieter Verhulst of the Netherlands has drawn my attention to the fact that the Lindner Technical Manual is online here.

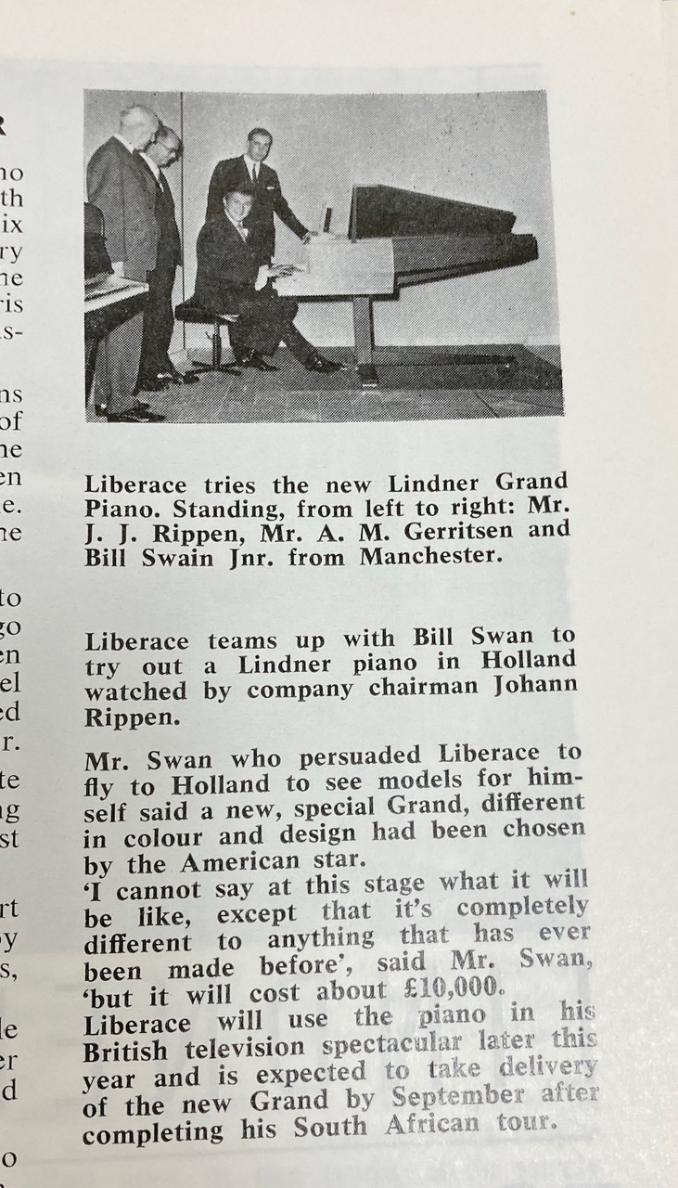

Stylish Lindner Grand - No Plastic!

Lindner also produced an interesting lightweight folding grand piano, with similar aims in mind. Below is an example, photo courtesy of David Winston at period piano

This beautifully designed and elegant grand piano doesn't have plastic parts! It has an excellent conventional Schwander grand piano action and will last as long as any other grand piano. It will be a superb feature in the right room.

A drastic end for a Lindner upright:

Additional Information:

Mr James McCabe of New Bruswick and Costa Rica has been in touch, and relays this interesting information. Mr McCabe was involved in the piano trade for years and I reproduce his comments with his gracious permission:

"I met Mr. Rippen at his factory in EDE Holland in the late sixties and later toured the Lindner factory in Shannon.

Mr Rippen told me at that time about the huge number of problems with the plastic action parts which were breaking all over the world. Probably they used styrene in the first action parts. Pratt Reid in the USA also made some actions with styrene flanges with the same problems of becoming brittle with ageing.

Mr Rippen told me that he switched plastics to an acetal resin (Delrin from Dupont) to correct this major flaw. The centre pins had to be specially made with a closer diameter tolerance than the standard centre pins for cloth bushings which are more forgiving.

Probably the Lindner you found in perfect shape was one of the later models with the delrin butts and flanges.

Alfred Knight tried rather unsuccessfully to use nylon jacks in his upright models.The problem that arose with the nylon (unlike Delrin) is that it is moisture absorbent and swells. Alfred then tried the nylon impregnated with graphite and the jacks were still getting stiff in moist conditions, so in the end he had to put standard cloth bushings in the nylon jacks which rather defeated the whole purpose".

August 2015:

Monsieur Alain Denis in France has done some interesting work on a Lindner. M. Denis is a Model Aeroplane engineer. Three years ago his son, a musician, rescued a Lindner piano. They set about a restoration, using a 3D printer to make replacement parts.

The whole process is beautifully explained and illustrated with photographs, on his Wordpress blog. There are two parts to the story. M. Denis has kindly given me permission to post the links here. Part one describes the problems and illustrates the broken parts, and Part two shows the making on the new parts and the completed project, along with this Youtube video: